The Freedom Riders View From Inside a Jail Cell

5,069 total views, 1 views today

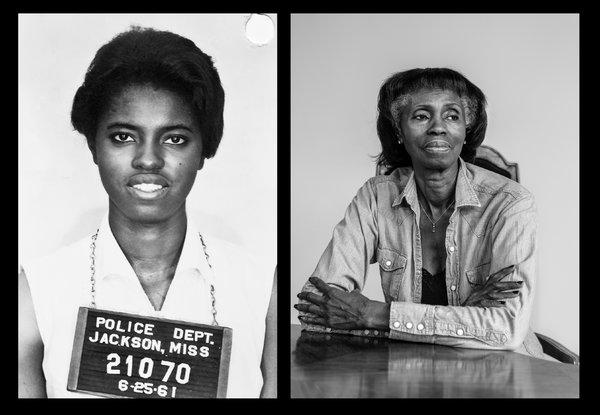

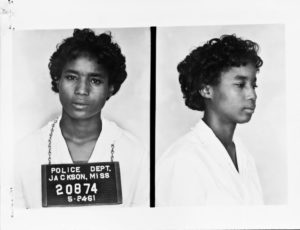

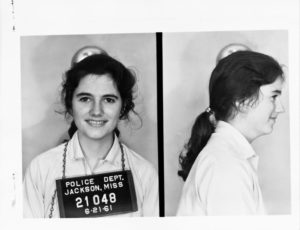

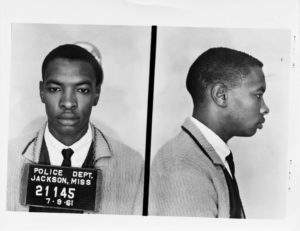

Eric Etheridge rediscovered the iconic mugshots of the freedom riders in 2003. The American columnist and photographer, while working on a photography project revolving around iconic images, recalled that the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, founded in 1956 to fight integration had been obligated to make their records open. With the help of Sarah Woodrow at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, he was able to retrieve these mugshots. It is fair to say these photographs had been relegated to the background of black history before Eric encountered them.

Eric did not understand the photographs at first glance. However, after careful consideration, he realized that what he had in his hands were records of everyone apprehended on May 24, 1961, when the freedom riders departed Montgomery for Jackson, Mississippi. Those who attempted to use the facilities reserved for white people were nabbed for trespassing, and more than 300 riders were sent to the Mississippi State Penitentiary, also known as Parchman Farm. A document containing the details of each rider was attached to every mugshot.

These mugshots and subsequent interviews with those captured in Jackson, shape the core of the Etheridges’2008 book, Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders. It chronicles a progression of in-depth interviews with the riders included in “Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders,” a photo-history book. Here are a few of them.

Mimi Real

We really needed to have our day planned out at Parchman in light of the fact that if we didn’t, we’d all be making noise and the din would be inconceivable. There were periods of calm, and there were periods where something organized going on.

In the evenings, we had a radio show. It was usually something theatrical, and every cell had to have a presentation. It could be anything from telling a joke to preaching from the scriptures. We were offered a bar of really horrible soap, and we’d make commercials in jest, about how you needed to use the soap if you wanted the brilliant skin. That was usually the best part of our day.

I was summoned to the interrogation room to be cross-examined by the Sherriff’s deputy. At least that’s who I thought he was. He had all the stereotypical looks of a redneck. He made all the standard inquiries first, like name and social security number. Anything else, we could decline to answer politely.

At this point, he wanted to know about my personal life. He asked whether I hung out with black boys, then he asked about my religion. We could have chosen not to answer those questions, but CORE suggested that we do, just to prove we weren’t atheist communists. I thought about it for a while, but in the end, I decided to tell him the truth that I was Jewish. He scoffed at me and said, ‘Oh, so you are a Jewess.’

I don’t remember replying to him. I was so dumbfounded that I just stared at him. I had never heard that term used in a discussion before, so I had no idea what he was talking about. Then he scoffed again and said, ‘so, you think you’re the chosen people. You think you’re better than everybody else.’

Again, I was dumbfounded. I still did not utter a word. Thankfully, he went on to the next silly question, and after a while, he let me go.

Larry Bell

Deputy Sherriff Tyson ran the show back at Parchman. He had a racist look about him, and everybody flinched when he spoke. There was another guard named Sergeant Storey who was older. At some point, they took our clothes from us as punishment and we sang the old Freedom Rider songs in protest. That got to them so they thought to teach us a lesson by letting mosquitoes in, turning off the air conditioning when it was hot and turning it on when it was bitterly cold. Every now and then, they’d allow us use the shower and we all had to shave with one razor. That was full on torment!

We had three meals every day. Cold grits and something like biscuits in the morning, sometimes bacon, but it tasted really bland. But we did not have an alternative, we had to eat it. There were almost never any vegetables so I lost a lot of weight, and because I wasn’t allowed to go outside, I lost a lot of coloration too. It was a harrowing experience.

We were protesting one night, and Sergeant Storey calls Deputy Tyson out. He opened up the cells and transferred about 35 of us to the ‘box’. The box was a room much smaller than 12 – by -12 and they stuck the lot of us in there. That was when I think we came closest to someone’s death. There was no ventilation and it got so hot that water was dripping down on us from the ceiling. They believed the torture would break us. When we didn’t break, Storey, through a hole in the wall, demanded that we tell him “Yes, sir” before he let us out.

We had no disrespect or respect for him, so we didn’t. That was when we heard the sound of the air conditioners going off, and rightly some people got concerned. I found a slit on the door, and we all took turns breathing through it.

Deputy Tyson came back in, still demanding that we say “Yes, sir” to him, to show respect for his authority or he was going to leave us in there till we died. At that point, a few people did. They let all of us go out anyway.

We had the chance to spread the word about our movement in Parchman. Not just casual conversations, but strong debates. The officials from the prison would often come in to listen. I’m not sure it changed anything in them, but they listened and did not interrupt.

Jean Thompson

We were transferred to Parchman after being taken to the city and county jail. The city jail had bugs, but I had to adapt quickly. I didn’t have the luxury of showing any fear. Some people were bailed out, and when our numbers started decreasing, we were moved to the county jail.

By the time we got to the penal farm, I was the only female left. We were interrogated and then given the rules and regulations. One of them was that we had to say “yes, sir” and “no, sir”. My parents brought me up not to say “yes, sir” and “no, sir” to white people, and so I was determined not to.

The six feet tall superintendent, who must have weighed about two hundred pounds, compared to my ninety at the time was interrogating me. I would answer yes or no, and avoid saying the “sir” by elaborating on my answer. He came up with a question while we were sitting at the table and I just said no. He slapped me so hard that I must have fainted for a few seconds. I readjusted after a few seconds and I said to myself that I wasn’t going to get slapped again because I might not last. After a while, he got tired, sent me away and called for someone else.

The FBI came in to investigate; because someone who got out reported that I and the others had been hit. After a couple of interviews with a few people, including the superintendent, they concluded that no one had been hit.